It’s a tax that has been increased six times since its introduction in 1994, but it often goes unnoticed by the public. This is convenient for the government as it has become a growing source of tax revenue. What is IPT? How does it affect buyers of insurance, and how much does it raise for the government?

A brief history of Insurance Premium Tax (IPT)

In the UK IPT is a tax paid when buying an insurance policy. It’s rolled up into the total cost of the insurance premium so often goes unnoticed.

Most non-life insurance products in the UK are not subject to VAT, but another form of tax was created to make up for this and bring us closer into alignment with other EU countries that already charged a tax on insurance. There’s an excellent paper from the House of Commons library if you want more background on IPT.

The tax was first announced in Kenneth Clarke’s 1993 budget, starting at 2.5% but has seen several increases in subsequent years up to the current 12% announced in the Autumn statement in 2016. There has been speculation in every budget about whether further increases are likely.

| Chancellor | Announcement Date | In Effect | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenneth Clarke | Budget November 1993 | 01/10/1994 | 2.5% |

| Kenneth Clarke | Budget November 1996 | 01/04/1997 | 4.0% |

| Gordon Brown | Budget March 1999 | 01/07/1999 | 5.0% |

| George Osborne | Budget June 2010 | 04/01/2011 | 6.0% |

| George Osborne | Budget July 2015 | 01/11/2015 | 9.5% |

| George Osborne | Budget March 2016 | 01/10/2016 | 10.0% |

| Phillip Hammond | Autumn Statement November 2016 | 01/06/2017 | 12.0% |

Table 1 IPT rates since introduction

How much does IPT raise for the government?

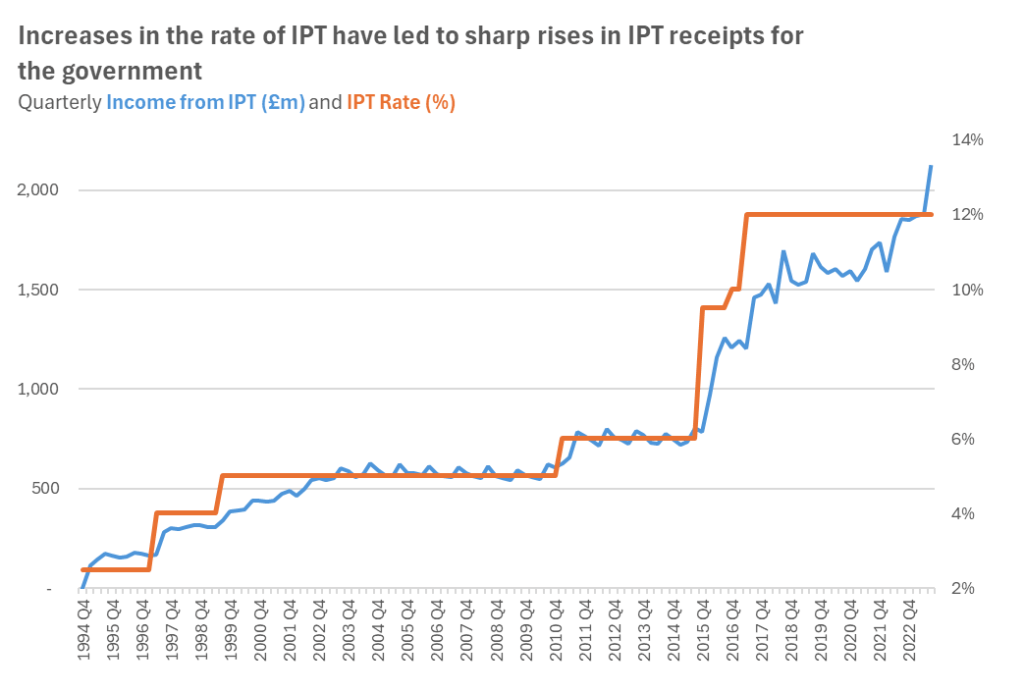

The graph below shows the government’s quarterly tax receipts for IPT (data from ONS) as well as the IPT rate since the tax was introduced in 1994.

The most recent sharp increases in tax receipts can likely be attributed to inflationary effects which have driven premium increases recently due to socioeconomic factors affecting supply of raw materials and labour, which are passed on to customers.

The overall IPT tax receipt for 2022 was £7bn, increasing to £8bn in 2023.

How does IPT in the UK compare to other countries’ insurance premium taxes?

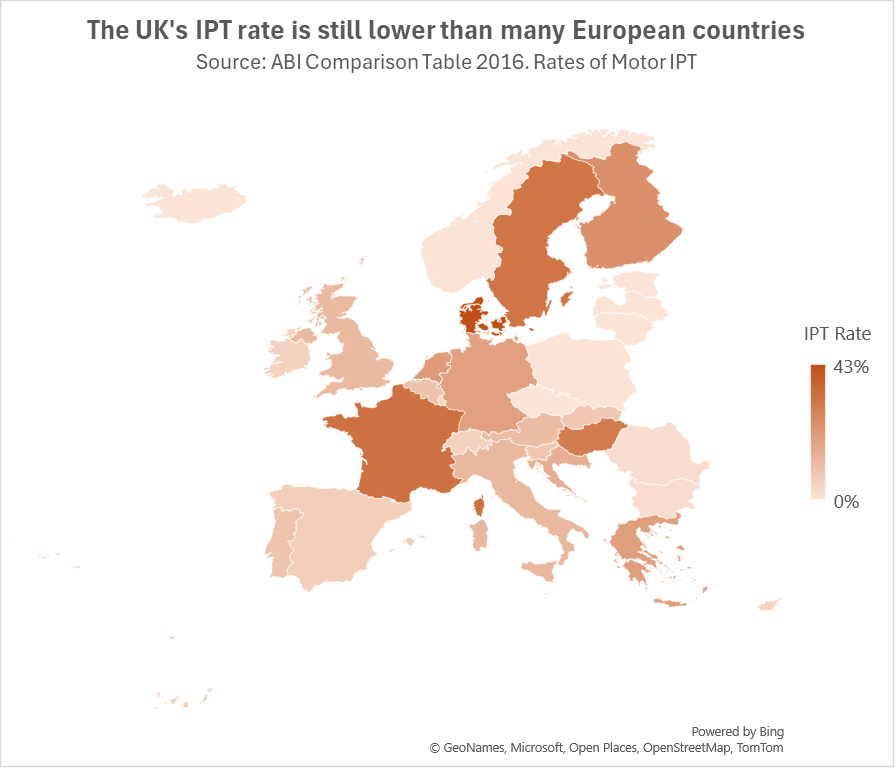

A direct comparison is not particularly straightforward due to the different rates of tax that apply to different types of insurance, and because some countries use different definitions.

Rates for each insurance product are difficult to compare, but using Motor as the most comparable product we can see that the UK rate is lower than most of Europe despite the recent increases.

The map below (based on some old ABI data) is likely a bit out of date now, but does illustrate the range of insurance taxes in place on motor insurance.

Is IPT actually a significant source of income for the government?

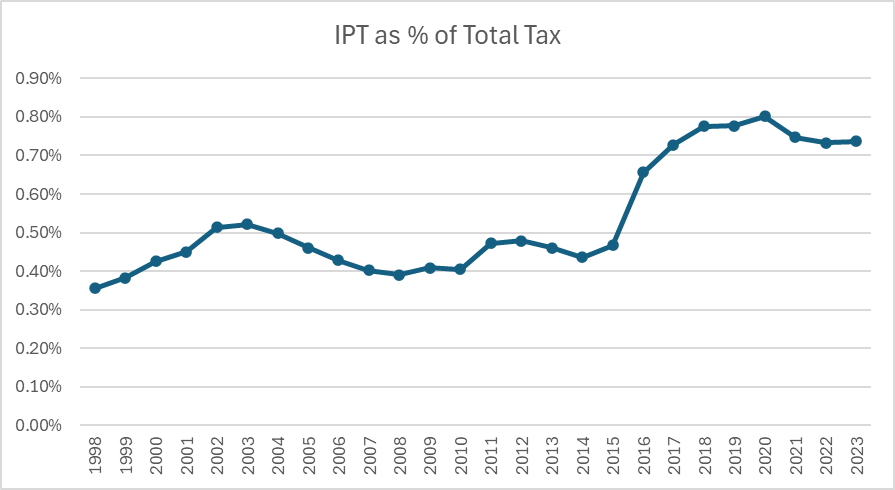

The short answer is not particularly. The figure above of £8bn in 2023 may sound a lot, but it only makes up about 0.7-0.8% of the total tax receipts.

It’s still a nice tax to have in the back pocket to raise a few billion at budget time that will largely go under the radar, especially if other tax changes get the news headlines.

The following graph shows the proportion of all government tax receipts that IPT contributes over time to put this in context.

Why did IPT increase, and will it increase again?

It’s an easy tax to increase because a lot of people won’t know about it, they may see it as something that only affects businesses, and people probably don’t notice it in their premiums.

Increases in IPT affect anyone buying non-life insurance, so all motor policyholders since that cover is compulsory in the UK, but unfortunately it also affects people who buy discretionary covers like contents insurance, pet insurance, possessions covers etc.

IPT hasn’t increased for a number of budgets now, perhaps in part because the tax collected from IPT has increased strongly recently, and further increases might seem excessive.

Lobbying by the ABI and other groups may also have had some effect. The sentiment amongst insurers is that this is a tax that should be reduced.

The ABI suggests that the majority of people don’t understand or weren’t aware of IPT. Leaving aside for now their questionable mascot, the ABI argues that IPT is a stealth and unfair tax.

The tax has already doubled in 10 years, so any further increases may be met with more opposition.

Why do IPT increases matter for policyholders?

Raising the cost of buying insurance is generally seen as undesirable as it discourages people taking precautionary measures to protect themselves from financial loss. Purchasing insurance, especially if voluntarily, is generally considered a responsible practice.

It’s worth noting that insurers do not absorb the cost of tax increases, they pass them on to customers directly.

Consumers are very sensitive to price, and increases may simply have the effect of making customers reduce their insurance spending by choosing not to buy the non-compulsory covers, or choosing to buy lower quality policies with reduced cover, which is risky.

Motor insurance in particular is compulsory (and to many a grudge purchase), so the cost of cover is increasing with no alternative. For some policyholders already paying high premiums this can add a significant amount to an already high premium, that is also a high percentage of their income.

An average motor policy costs £650, so IPT adds an extra £78 per year to the cost of insurance. This is particularly bad for younger drivers who pay an average of £2,041, so much more in absolute terms in IPT.

Conclusions

As IPT approaches thirty years since its introduction, it remains a contentious tax that many in the insurance industry think unfair. Sadly it’s not well known or understood by the public so it’s an easy tax to increase without drawing much attention.

On the positive side, it’s still well below the rate in many EU countries, though there may well be other factors that complicate that comparison.

It’s certainly worth watching out for any changes in future budgets.

Further reading and references

- Notice IPT1: Insurance Premium Tax – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- Insurance Premium Tax & Insurance Guide | Compare the Market

- Insurance premium tax (parliament.uk)

- ABI IPT comparison table: https://www.abi.org.uk/globalassets/sitecore/files/documents/publications/public/2016/keyfacts/euipt.pdf

- Public sector current receipts: Appendix D – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

Leave a comment